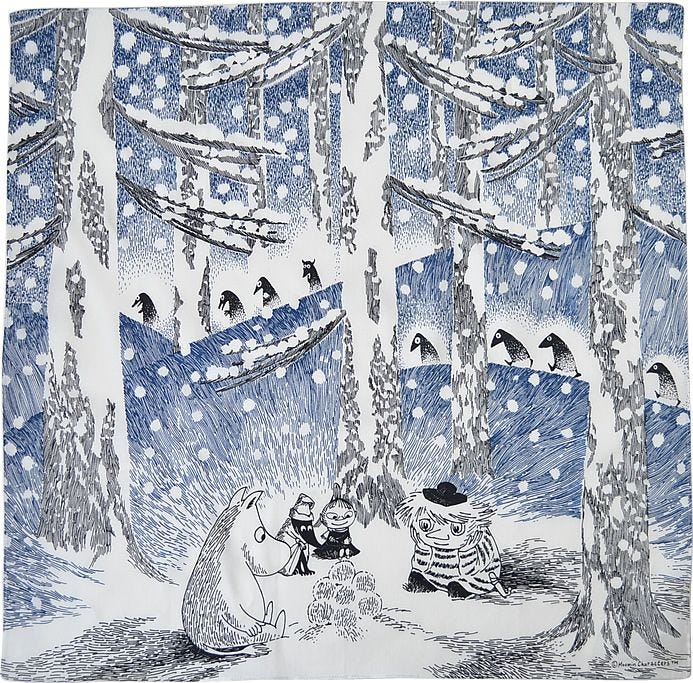

Inside the dark forests of the internet

This is the second part of a series on the identity of social networks:

Part two: Inside the dark forests of the internet

If you’ve been hanging for long enough in the tech-intellectual internet corner, you’re probably acquainted with The Theory of The Dark Forest of the Internet—which was published a few years ago by Yancey Strickler.

As it suggests, the internet has become a hostile place for its natives. When you swipe through a friend’s story only to be interrupted by an ad or receive likes and spam messages from bots, it’s no wonder many have minimized their social presence and gone silent. The meaningful internet has gradually moved into more private and hidden spaces: scattered dark forests, far from the public eye. As Yancey puts it:

In response to the ads, the tracking, the trolling, the hype, and other predatory behaviors, we’re retreating to our dark forests of the internet, and away from the mainstream.

The theory has made waves across the vast internet ocean, sparking interest and many riffs including the beautifully illustrated The Dark Forest and the Cozy Web by Maggie Appleton, and The Dark Forest Anthology of the Internet, a collective book published by Metalabel last year.

In fact, the original Yancey’s post itself was built on another idea: The Dark Forest Theory of the Universe.

Another related-unrelated notable post is The Extended Internet Universe where Venkatesh Rao coined the term cozy web:

The cozyweb works on the (human) protocol of everybody cutting-and-pasting bits of text, images, URLs, and screenshots across live streams. Much of this content is poorly addressable, poorly searchable, and very vulnerable to bitrot. It lives in a high-gatekeeping slum-like space comprising slacks, messaging apps, private groups, storage services like dropbox, and of course, email.

I’ve been exploring the cozy web at length in the previous part, and now, as I write my own riff, I take these ideas further, asking:

What’s inside the dark forests of the internet?

Email

I’ve been using emails ever since I’ve had an internet modem. But if to be honest, I’ve never really thought about it as a resort from the public and noisy internet. To me, email has been strictly related as a private and very formal channel to mostly meet internet strangers—whether for professional or personal purposes.

Although I don’t think that’s a completely wrong observation, it certainly misses something, perhaps more profound. And I guess the fact that I’m not that email power user, chasing after the inbox zero mission has made me unconsciously neglect it for its healthier qualities.

But a few weeks ago I came across Craig Mod's musings on social media:

Me? I’m doing email. (And not the Substack kind.) I am SO GRATEFUL FOR EMAIL. Good lord. I love email. I love “stupid” email services. I love inboxes. I love it all so much.

I love that these systems don’t smash concentration (well, email, somewhat, sure; but nothing like an algorithmically activated feed of dingdongery) and support creativity and are DURABLE and sustainable (as proven by history).

This also prompted a self-reflection.

Reading those lines, I'm reminded that long before all the news feeds and mobile-software mania, there it was: a simple protocol for sending and receiving digital messages. Beyond its primary role of communicating with colleagues and friends, it’s where memes and PowerPoint slideshows first took off.

As a teenager, trying to increase my ratio buffer on torrent sites, I used to cold email remote hosting companies, offering to barter my design skills for server access. And before we knew what “likes” would have become, I remember times when I was nervously sitting right in front of my computer screen, waiting for emails to land in my inbox. Email was my first glimpse into online exchanges—and to this day it remains a primary way to communicate over the internet. I still use it to reach out to people, respond to newsletters, and connect people through intros (more recently, thanks, Alex Dobrenko`!).

However, the email interface isn’t a social gathering space; it’s more like a café meeting table—an intimate setting where conversations are intentional.

We’re so accustomed to thinking of social media in terms of MMORPG—always-on, and endless. But since email is more low-key and built for smaller interactions, it kind of lost its social vibe. As we moved away from 1:1 communication, email has taken shape as a more serious, private space, serving our real-world outie while social media has captured our innie’s lives.

As email solidified its role as an all-in-one personal and professional hub, it also became a target. The flood of SaaS platforms has turned inboxes into battlegrounds for attention, polluting them with dark patterns of unnecessary noise:

You might think you hate email. You don’t. You hate spam, and you hate work. I also hate spam, and I also (mostly) hate work. These things are not a necessary part of email - and with just a few good choices, you can more-or-less abolish them entirely.

The definitive guide for escaping social media (and joining the indie web.)

Invading our privacy (I’m looking at you, LinkedIn) has turned email into a never-ending unsubscribing game. For many, this has made email overwhelming—hard to check, and harder to navigate. However, and despite the abuse, email has been the most reliable and effective tool for leveraging the internet, outlasting all other “modern” social inventions, it likely has the largest amount of customers, more than any multi-trillion behemoth.

As Ryan Gilbert recently wrote in launching his new newsletter:

I couldn’t confidently tell you if Twitter will be around in its current form 6 months from now… but I know email will be.

That might be why some tech-savvy groups still use email the old-fashioned way. An interesting local example here is YACV (short for Yet Another CV), which serves as a job search and career forum for veterans of the IDF's technological units. It’s a private social network that runs entirely on Google Groups—via emails of course.

Most recently I also discovered Bits and Bobs—a weird breed of a weekly newsletter-blog, published in a shared Google Doc by Alex Komoroske. When subscribing to its Google Group, you get notified by email as well. And it magically works. Every time I check the doc I can see at least a few users lurking across the bullet points, and to be honest, I find it peaceful. It’s detached from any feed and engagement metrics.

The interesting part of this gdoc, from a social perspective, is that it doesn’t live only in a read-only mode. Viewers can also comment, and from the short time I’ve been following it, in a very thoughtful way, which leads to another social component that has long carried a bad reputation.

The comment-verse

Comment sections on public social and news media websites are arguably the most disreputable corners of these platforms—unfiltered, unrestrained spaces for people to spread anything but wisdom or positivity. In fact, some major media outlets have already disabled comments almost a decade ago as the chaos went out of control.

But once again, Craig’s words struck a chord:

Oh, and amidst the muck, Kottke’s comments section is a joyful haven.

Thinking of other blogs and communities that are more familiar to me—whether it's the design critiques of Brand New, the philosophers of LessWrong, or the sharp-tongued but engaged communities of Hacker News and Reddit—they all share the Kottke’s spirit.

As it turns out, applying the same dynamics to smaller, cozier spaces has the opposite effect of large-scale platforms—it cultivates meaningful discussions.

One example I particularly like comes from Brand New—where designer Emunah Winer started as an active commenter on the site’s posts and eventually became a speaker at one of its conferences:

5 years ago I started commenting on @brandnewbyucllc reviews to try to squeeze my way into a design world I did not think I belonged in. I snuck my way into the types of conversations I never had at design school because I never went to design school. I commented on projects from agencies I felt I could never work at.

This year we'll be speaking alongside some of those agencies at the 2023 Brand New Conference in Chicago. This is quite literally my dream come true.

Unlike social media and large media platforms, where words often get swallowed into the void, the cozy web thrives on intimacy.

This positive pattern extends to small-medium blogs like those of Cal Newport, Ribbonfarm (pre-retiring), Tom Critchlow, OM, Erik Hoel, and many other self-hosted and Substack blogs. It’s the long tail of blogs that yields a much better online atmosphere.

In PBS of the Internet, Laurel Schwulst makes the case for the need for “PBS energy” internet, wondering:

Who is the Mr. Rogers of today? Maybe “PBS of the Internet” is about curating existing influencers online and distributing this curation widely.

In many ways, these kinds of blogs and small communities share the same energy. Detached from the noise of public social media, they function much like PBS: free from algorithmic pressures and advertiser influence. Built on more modest incentives, they naturally invite deeper and more authentic conversations.

New Person, Same Old Mistakes

Dark forests aren’t strictly havens—not in public comment sections, nor in private emails. After all, you can’t separate human spaces from human nature. Depending on the forest vibe, conversations can feel like a battle, laced with cynicism and sarcasm. But more often, these spaces serve as fertile ground for diffusing a much needed positivity into the internet’s air.

In a high-rated capitalistic world, perhaps much like PBS, we’d all benefit from un-monetized online spaces where incentives are guided by human ethics rather than profit. Maybe there’s an infrastructure waiting to emerge—something that could make dark forests a little less dark.

One day we might all walk outside under the digital sun, experiencing the cozy warmth online vibes without feeling the need to hide from predators.

After all, no one owns the internet—we share it together.

What’s your dark forest?

—Itay

If you found this piece useful, feel free to share it in your favorite internet corners. Also, consider supporting my work by inviting me to a virtual coffee or subsidizing my gym membership.

In case you missed the first part:

Looking for humanness in the world wide social

When I look at the current form of social media, it all feels dumb: watching adults post nonsense or praise “influencer gurus” while doom-scrolling from dusk to dawn seems absurd. We should have had more important things to do with our lives, yet we’ve all gotten caught up in this utopian-dystopian era.

Great thoughts, great links!

Love all this. For me I try to live by “the internet is a tool, not a destination.” I want to meet people using the tool, then continue the conversation elsewhere. Sure, email and Zoom, but then occasionally in person, at an event, over coffee.

Kinda like the small town life I live now. I can be in NYC in 3 hours. Meet up with some pals, do all that. But then I come back home, to my (quiet) inbox. No DMs to check. No pings from replies on various social media platforms (or LinkedIn telling me “someone” viewed my profile haha).