head on the cloud, feet on the ground

A conversation with Sari Azout of Sublime

I’ve long been intrigued by the journey of Sari Azout, ever since she announced Startupy a few years ago, which later became Sublime, a social knowledge management tool for collecting and connecting ideas.

I’ve had a few conversations with Sari in the past, but this time, I sat down to interview her about her perspective on business and life.

As we began our long conversation, the sound of the local produce vendor shouting beneath my apartment made for a fitting backdrop. We discussed what it means to design a sustainable and humble company these days, while still anchoring a big vision in grounded reality.

Excerpts of this interview will also be available in the Niche Design zine.

Early days

Itay: Your path into tech has been somewhat traditional. You worked in VC, but you've since veered in a very different direction, building something outside the typical venture model. Plus, you live in Miami. Could you share a bit about your early days and what led you to go that way?

Sari: After college, I took a traditional investment banking job. It was my first role, and it allowed me to stay in the US. At that time, I was really just focused on how to stay in the country, not on what I personally wanted to do. So I did that and checked the box. Once my visa was sorted out, I started a company in New York.

What I mainly love about startups is that you can't hide behind buzzwords, as your ideas collide with reality. Writing about something is one thing, but when theory meets practice, it’s a different story.

After doing the startup thing, I worked in venture capital and ran a strategy team at a startup studio. I really enjoyed those roles because I got to see so many teams building interesting things. But the whole time, I kept thinking there’s so much bullshit in this world. I started to develop an allergy to hype and all that stuff.

Also, it became too much of a comfortable job. I could make PowerPoint decks in my sleep and craft compelling investment stories, but it felt hollow. I realized I was good at storytelling and condensing ideas, but I was tired of not being on the hook for implementing them. I wanted to work on something where I could still explore and write about ideas, but also make things. Moreover, feedback cycles in venture capital are so long—you can make a terrible investment and not know for 10 years.

So I embarked on a fuzzy journey to figure out what is me, and what I can do. And I’d say I’m still on that journey.

Itay: I remember you first appeared on my Twitter timeline with Startupy. You compared it to Roam Research, right when that whole tools for thought hype cycle was peaking. How did the first cycle of Startupy actually come to be?

Sari: Startupy really started as a side project, as I still had a full-time job at the time. The insight for starting it came to me while writing the CYP newsletter, as I had been curating a repository of ideas and insights for a while, in single-player mode, meaning only I had access to it.

Startupy is as if Roam, Wikipedia, Substack, and Product Hunt had a baby.

One day, I decided to sell access to it through the newsletter. I just said, “Hey, I have this curated repository of ideas”, and it did really, really well. That sort of awakened this thought in me that people are willing to pay for curation.

I then started wondering why people were paying for that, and I realized the main reason was because search sucks. You can’t find this stuff on Google—it’s too niche. The indie web isn’t indexed properly. The content on the internet’s edges isn’t SEO-optimized. Then it became clear there was real demand. But I also started asking why so many people are doing this work in single-player mode?

Startupy, to me, was an exploration of what it might look like to build a space where we all curate together.

You asked earlier about hype and buzzwords. It's interesting—there's so much of it, and there’s definitely a lot to critique. But I also think humans need to give things labels to make sense of them. Whether it's the creator economy, the experience economy, or the ownership economy, people throw around these terms all the time. It’s a lot easier to raise funding today if your deck talks about AI agents for example. A few years ago, it was all about building a D2C brand—try to fundraise with that today…

With Sublime specifically, I don’t care if it’s part of the current hype cycle, because I’m a lifer in this. To me, it’s a journey about finding a home for my ideas. Yes, they’re rooted in a feeling of aliveness, creativity, and sublimity—and yes, it’s about knowledge management, but more than anything, it’s about following what makes me come alive rather than following the labels.

Is that a venture-investable opportunity? Probably not—though maybe someday in the future. I’m not interested in “go big or go home”, but I’m also not opposed to scale.

I sit in the intersection of someone who genuinely loves technology but is also very skeptical of it. That makes me engage with it more thoughtfully.

A lot of people write about tech and criticize it, but my issue is that it’s hard to have a respectable opinion if you’ve never been in the trenches building something. For me, it’s about being thoughtful, having a writing practice, putting ideas out there, and also maintaining a solutions-oriented mindset. Not just critiquing, but proposing alternatives. That’s the sweet spot I want to inhabit—indefinitely.

Itay: I imagine your background helped with raising money for Startupy, but there’s this conflict between building a so-called “niche” product and the expectations of venture funding. How do you convince people to invest in something that isn’t centered around making a lot of money right from the get-go?

Sari: Our pre-seed round was mostly small checks from a lot of different people. That’s very different from having one lead VC who expects you to raise another round in 18 months, and then another after that.

We raised at a stage when it was less about hitting specific milestones and more about belief in the team and vision. I think we were lucky in the sense that we were able to convince people supporting us without feeling a gun to our head in terms of aggressive growth targets. We were also very honest about how we were going to build the company—we made it clear that this might be a one-and-done.

I think the binary of “bootstrapped” or “venture-backed” is inadequate. There’s a whole spectrum in between. We did need resources to start.

Are we playing the lottery? No. We’re trading scale and speed for freedom. That was a conscious choice. But I also believe there's a way to build a very valuable company slowly. If you look at someone like Brunello Cucinelli or other old-school luxury fashion brands, a lot of them took decades to build. I think we can compound slowly and still build something meaningful and valuable.

But it is atypical. We don’t fit into the classic venture-backed model, but we’re also not fully bootstrapped either. I actually think there’s a growing group of people who are building with sustainability in mind—people who are values-driven, who want to stick around for a long time.

A lot of VC funds have a fiduciary responsibility to return the fund, so they need to find those unicorns. But there are also a lot of people out there with different agendas. People who want to see amazing things in the world. Who knows, maybe in a few years, we knock on Patrick Collison’s door and say, “Hey, we’re building this thing, these are our values. Would you give us $3–5 million to keep going?” We’re not promising massive growth, but we are building something beautiful and enduring.

If were a high-net-worth individual, I’d be backing more and more projects like that. So, I don’t know exactly how it will pan out, but I know that we’re building to exist first.

Itay: Do you think those investments were kind of a gesture to you? What was the narrative that resonated with them?

Sari: Since we started the company, the big story was kind of twofold. The first idea is rooted in this long-term vision of building a human-curated search engine of sorts. If you're a writer, freelancer, designer, or any kind of creative professional and you're looking for interesting references or ideas, trying to see what thoughtful people are saying about X, Y, Z—where do you actually go online? That question drove a lot of what we’re building.

Sublime is a knowledge management tool where people connect things like their Kindle, Readwise highlights, and Twitter bookmarks—this is the kind of stuff you find on Sublime, which isn’t easily found anywhere else. We also embraced AI to make the search really good, and it became a very interesting, investable use case that got people excited.

The second idea is about how we can use the context in your library to power conversations and interactions with LLMs. The problem with generative AI is that it’s contextless—it’s mediocre by default. But if it understands my references, my taste, and my point of view—a lot of which lives in a personal knowledge library, then it becomes way more interesting.

You can pursue those ideas in a venture-scale way—we're just choosing to take a more artisanal path. I think people have to believe in how we're doing it, which is more bottom-up and community-forward. Like, the first 1,000 paying customers came straight from Substack, and I personally onboarded each one. Was it the “right” decision? I’m not sure, but it felt right for us.

I think more about what's the most me thing, or most us thing as a team that we could do. It’s about putting on blinders, closing your eyes, and asking: what’s the thing that doesn’t exist yet but really should?

That approach has already attracted a group of people who believe in it and gave us the capital we needed. Now it’s on us to keep compounding and turning that belief into something truly valuable.

Itay: And what’s your relationship like with those first investors? Do you just send them regular updates, or are they more in the background, being available if you reach out?

Sari: I’d say it’s more of the former. I have relationships with all of them, but it’s a mix. We have investors who gave us $2,000, $5,000, or $50,000. It really runs across the gamut.

Some of our investors are well-known newsletter writers, like Packy McCormick or Sahil Lavingia from Gumroad, who’s built an amazing, sustainable company without going the traditional VC route. Others are people like a small publication’s editor-in-chief. We have a lot of different kinds of backers.

Honestly, what I consistently hear when I send out investor updates is something like: “I’m just happy to be along for the ride. These updates are amazing, and I’m so happy to support you.” It’s an interesting spot to be in—we control our own destiny, and we have this amazing group of people behind us. It doesn’t mean we have guaranteed follow-on capital, but we’ve got plenty of runway, and we can build with freedom and values at the center.

I kind of have this book in my head about how I hope this journey ends, and I’d love for us to become a case study for how to build a company that doesn’t fit neatly into the existing boxes. I’m still very much in the middle of it, so I don’t have all the answers, but I’d love to live to tell that story.

Itay: It reminds me of something Anjan said to me. When he started Daylight, he thought smallness was an idea people were willing to build around. But over time, he realized that most people are more ambitious than staying small for its own sake. Can a company like Sublime exist in that middle space—something purposeful and sustainable, without having to scale endlessly to meet traditional investor expectations?

Sari: I definitely think some of our investors came in expecting a return. Also, I don’t view smallness as a badge of honor. It’s not like we have to stay small because going big is a virus. I actually think it’s admirable to build a company at the scale of Amazon if it works and delivers value to a lot of people.

Philosophically, I don't have anything against scale per se. What I’m against is taking shortcuts, and at what expense. Say I decided to take Sublime and start paying random influencers on TikTok to drive 500,000 downloads—I could probably do that. Then I could call it a VC play and raise money on the back of those numbers. But that would likely mean low-quality downloads, without returning customers.

There’s a kind of purity we want to retain when it comes to building a real business. A lot of people in VC don’t build real businesses. They just build them to have all the optics of being investable. That’s not what I want. I want to build an infinite game—a sandbox for creating extremely valuable things.

But I’m not dogmatic at all about size. Our investors should get a return on their investment, and Sublime should touch more and more people over time, as long as we get there in the right way. There’s a very easy way to artificially reach more people, but we’re not chasing just metrics; we seek real resonance.

head on the cloud; feet on the ground

Itay: I want to enter this topic of the “new” vs. “old” world. After years in tech, I’ve grown tired of the typical startup culture and its lingo. You represent to me the old-school founder archetype. You’re still using the classic language, but in a way that feels more grounded and intentional.

What’s your perspective on the tech-startup culture these days?

Sari: There’s a lot of status associated with saying you're a founder or that you work in AI, or whatever the trend du jour is. Years ago, graduating from college and going into investment banking was the cool thing. Now it's working at companies like Facebook, Google, OpenAI, or whatever’s considered “hot”.

Typically, when something confers status, it attracts people who are focused on winning short-term games. That inevitably brings a lot of noise, and maybe disgust is a strong word, but it does turn people off.

I’ve been in tech long enough to know that hype and status come and go. To me, it’s more about thinking about how to build something that stands the test of time.

To me, that path should be contrarian. It’s interesting because tech used to be about making bold, contrarian bets. Today, it’s more about fitting in, so going against the grain takes real courage. VC, especially what you see on Twitter and elsewhere, is mostly herd mentality. Most people have no idea what they’re talking about—they just look at who the big names are investing in and follow along.

You mentioned Anjan from Daylight before, and one of the things he said was that so much of what made Silicon Valley special in the past was backing the non-obvious things—bets that weren’t inevitable. If Anjan hadn’t started Daylight, it’s unlikely anyone else would have. Compare that to realtors selling real estate—if one doesn’t sell a house, someone else will. That shift, from making big bets to play it safe, speaks to a broader risk aversion in the industry. There are far less people trying interesting things. Many talented people are just optimizing ads on Meta.

So, you can choose to look at the bad stuff, or you can realize there’s not a lot of real substance out there, and decide to build something with longevity and sustainability. It’s not necessarily easy; part of the challenge is making it exciting enough for people to join in. But you do get to choose how you show up in the world. You can sit around and complain, or you can just build something real and great.

We’re definitely not building Sublime in a particularly popular way. It’s very old school: slow, steady, and hard-earned work with no shortcuts.

At the end of the day, humans run on stories. And while many stories have managed to cut through the noise, it’s up to people like you and me to offer alternatives—stories that are just as compelling.

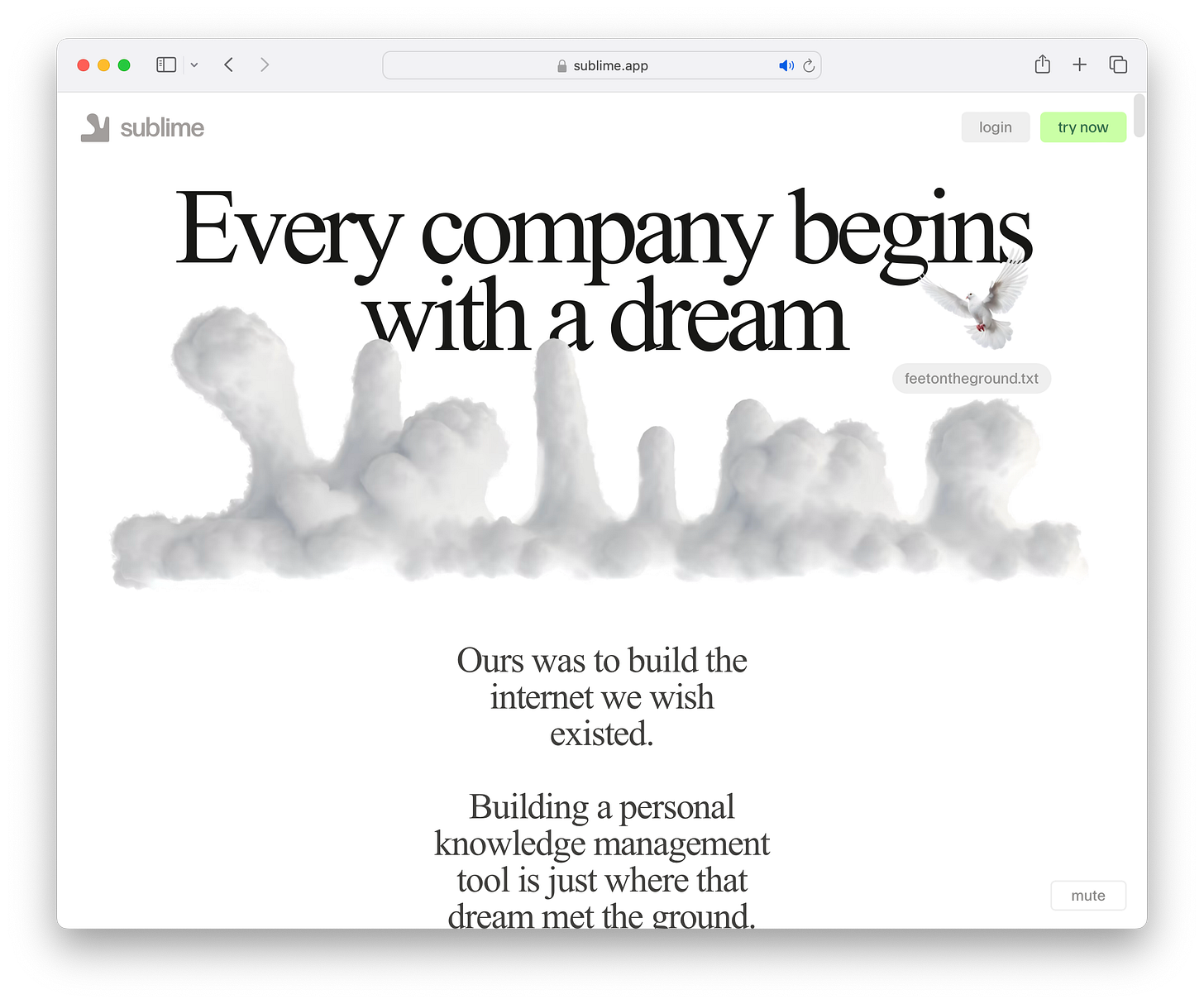

Itay: Speaking of stories, when I look at Sublime’s homepage redesign, the way you articulate the story feels deeply vision-driven. Personally, I find it hard time think in vision. How do you craft a manifesto or communicate a strong vision without sounding overly dreamy or detached from reality?

Sari: I always say that we need to have our head in the clouds and our feet on the ground. We have to blend our aspiration with grounded utility. Our job is really to straddle that line very well.

If I think about the day-to-day at Sublime, most of the value we generate for our customers comes down to utility: Can I import my Twitter bookmarks and search them intelligently? Can I capture an insight from a podcast? Can I connect ideas in interesting ways? It’s very much about what we are doing, for whom, and how it makes their life better.

Genuinely, we make the people obsessed with Sublime better at their jobs. We make them more creative. These are practical outcomes. They don’t necessarily care what our vision is. We have to deliver on that grounded utility—having a grand vision doesn’t exempt us from walking the talk.

A lot of people make the mistake of being too dreamy. We try to stay grounded, but vision matters to a lot of things: it matters heavily for recruiting; it keeps the team aligned and excited over the long term; it helps with storytelling and top-of-funnel awareness; and it’s what wakes me up in the morning. The hardest thing in the world today is earning attention, and sometimes, utility alone doesn’t cut through, but a compelling story about the future can.

So it’s not binary—it’s about tastefully straddling the two, specifically in the PKM space, where everything tends to be so utilitarian and productivity-oriented.

I personally don’t feel alive or creatively energized by most of it.

What keeps me going is asking how we can bring the feeling of the Sublime into people’s lives. That’s rooted in feeling, and because of that, investing in some of these bigger-picture, fuzzier storytelling things really, really matters.

At the end of the day, it’s like: how do I want to be remembered? What kind of work am I making a sacrifice to spend so much of my time on, and why? As humans, I think we need that “why”.

Sublime isn’t a mercenary business opportunity. If it were, I’d be doing something else—there are far easier ways to make money.

Write and they’ll come

Itay: From what I’ve seen, you haven’t gone through the traditional “TechCrunch” coverage route—no big press splash, just appearing more in niche newsletters and podcasts. How do you think about marketing? And is the new podcast app an extension of that same approach?

Sari: When it comes to marketing, our main focus has been on writing. The more we write, share, and build in public, the more people are drawn to our work. That’s one thing we do consistently.

We also showcase how others use Sublime. We spend a lot of time with our community, learning how they’re using the tool, and sharing their stories. There has definitely been a lot of organic growth out of it. I believe if you build something beautiful and useful, people will share it—and we’ve seen that happen.

You brought up Podcast Magic. One of the big questions I have is: what’s the best way for a product like Sublime to grow? I don’t have the answer, but one we’re exploring is through creating these small, focused tools we call “drops”. Each one does a single thing well, and ties back to Sublime in some meaningful way.

Sublime as a whole is a pretty deep tool. It lets you collect things, connect ideas, explore them on a Miro-Figma-type canvas, and search across everything. It’s a big ecosystem, and it requires a bit of time and investment to understand and fully use. That means activation can be a little harder, but our retention is off the charts. The people who love Sublime are obsessed with it.

With something like Podcast Magic, it’s meant to be a lightweight, delightful entry point. For context: if you’re listening to a podcast on Spotify or Apple Podcasts and you hear something interesting, you just take a screenshot and email it to podcastmagic@sublime.app. You get an email back with the transcript from that moment and a video clip you can share. We then connect that to your Sublime library, so you can go deeper and explore related ideas.

These kinds of simple, viral products are a great way to grow our top of funnel. So we’re going to keep experimenting, building things we wish existed for ourselves, and seeing what resonates.

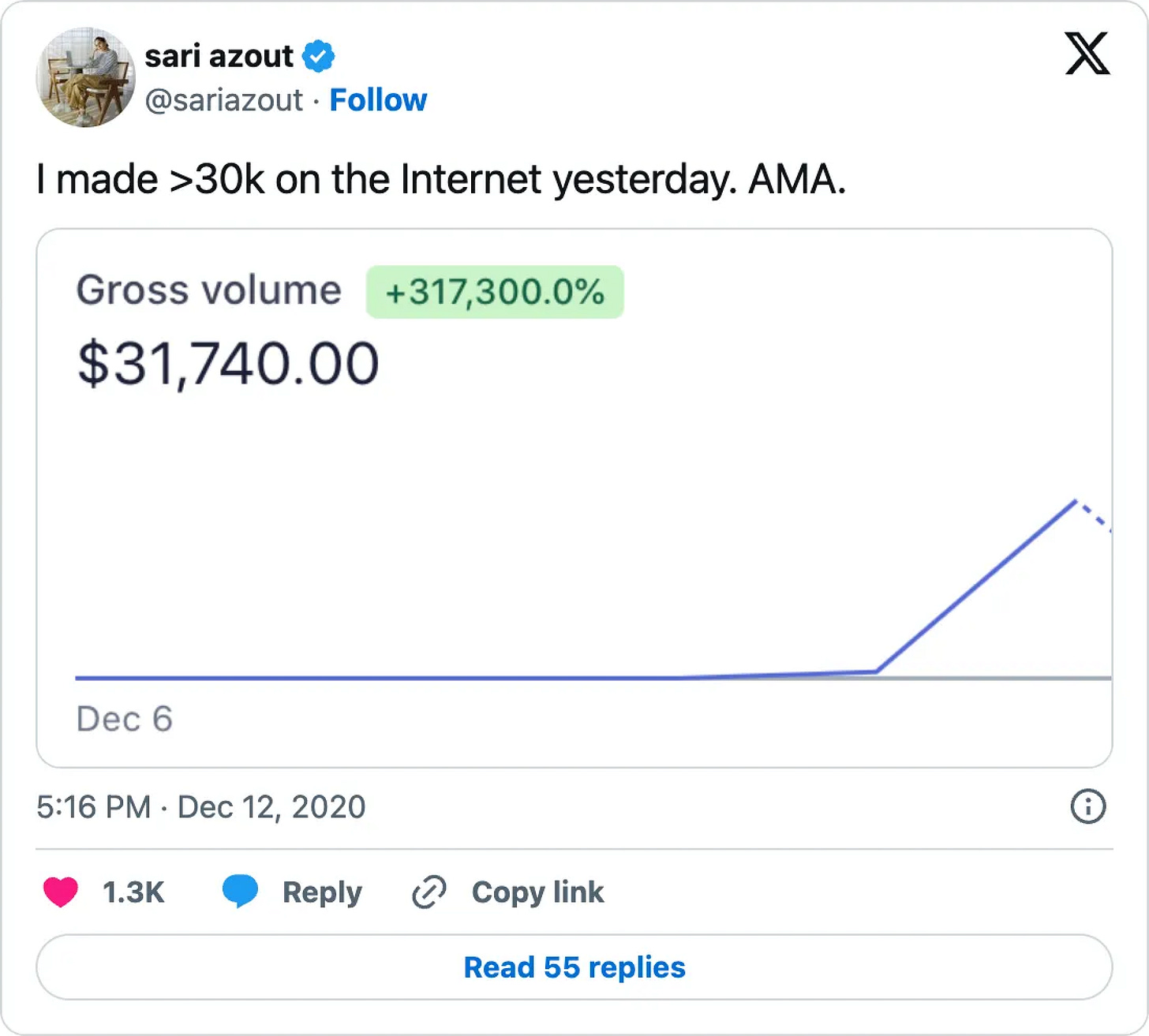

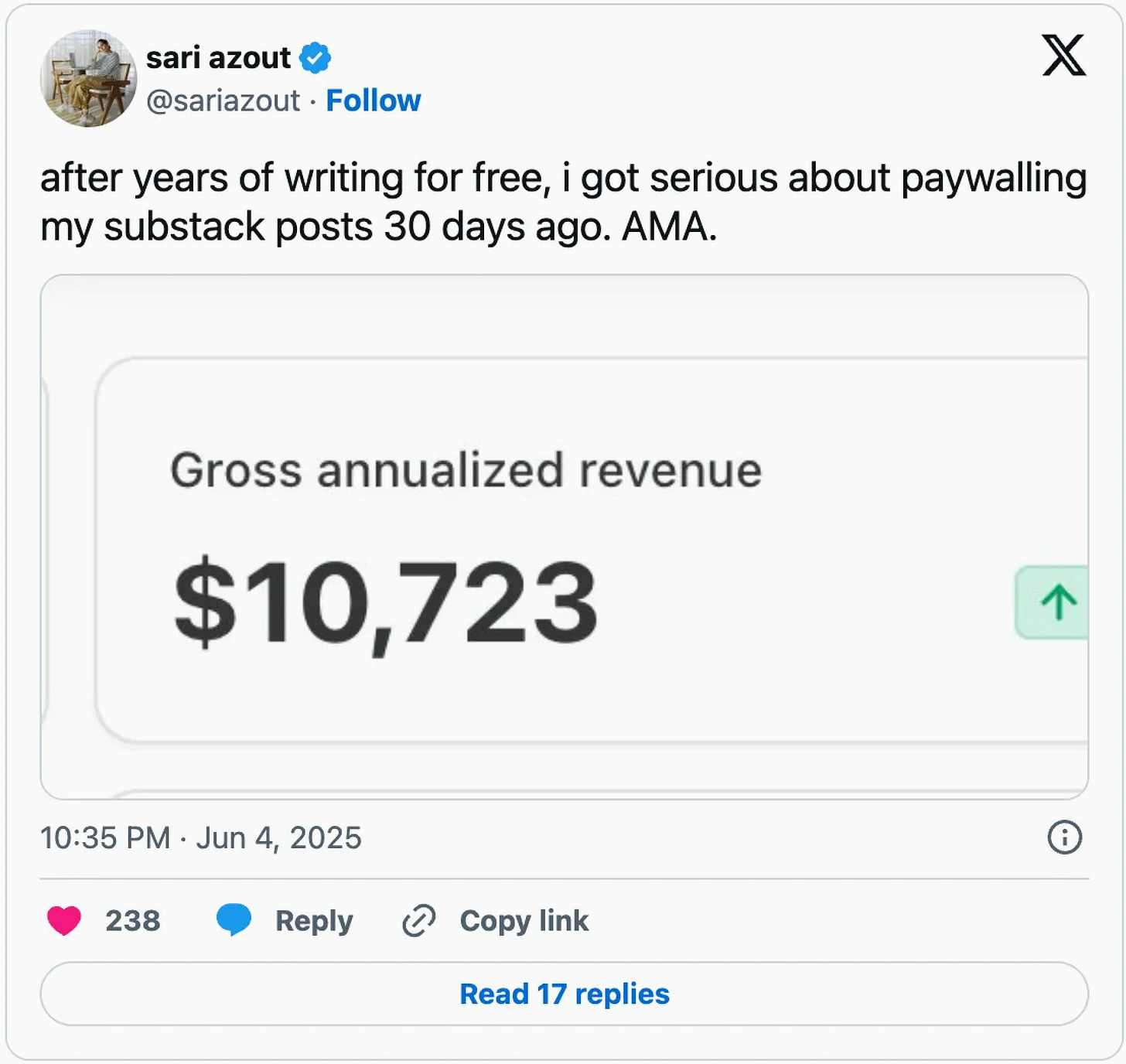

Itay: I was actually surprised to see how much revenue comes through just from your Substack. You also produced two longform zines. Do you see them as part of Sublime’s growth and marketing strategy, or more as a separate creative outlet?

Sari: I’d say we produce the editorial work for two reasons.

First, our team is just a bunch of people obsessed with interesting ideas, so we genuinely enjoy making zines and publishing our own original editorial.

It’s also an effective acquisition channel. If you look at our revenue charts, the months when we launched the zines were the same our revenue grew. People share the zines, so more people discover Sublime, and more people become paying users.

Also, they’re structured to be cost-neutral. In fact, they’re revenue-positive. If it costs us $6,000 or $7,000 to make them and we bring in $15,000, then it’s essentially a customer acquisition funnel we get paid for. It’s not super scalable, and it’s not what’s going to pay our team the wages they deserve, but it’s a very Sublime way of growing the company—honest, and authentic. So, from a business perspective, it’s been the smartest use of our time and resources.

Second, at the end of the day, Sublime is a tool to enable people to produce and create amazing things. The point of the tool isn’t just to collect ideas—it’s to create new forms of knowledge and meaning. We don’t want to get so caught up in building software that we forget to actually make things ourselves.

One of the big shifts I hope Sublime can support in our customers is to change their ratio of consumption to creation. We want to pull people out of passive consumption mode into creation mode.

We’re not looking at what Roam, Tana, or Notion are doing. We’re asking: what do we want to build? What feels exciting and alive to us? If we follow that aliveness, I think people feel it. It’s magnetic.

Itay: You mentioned the community aspect earlier, and interestingly, I’ve met a few people through the Sublime Slack—people I’d say I have a stronger relationship with than many others I’ve met elsewhere (s/o kev and Steyn Viljoen). Do you have an idea why the Sublime community feels so engaged?

Sari: To be honest, I have no idea. But I love hearing that you’ve made friends through Sublime! What’s so interesting about software is that most of the time, we don’t even know these kinds of things are happening.

Just recently, someone tagged me in a Substack post where two Sublime members, one interviewing the other, talked about how they met through Sublime and bonded over their shared love for it. There’s something really powerful about meeting through a product, collaborating, and building a connection that way. I don’t really have a way to track it, so I rarely find out when it happens, but it speaks about the fact that we’re not just building a utility. Because we’ve been so explicit about our values, by proxy, there’s this beautiful side effect. By joining Sublime, you signal that you care deeply about creativity. You engage with ideas, and you have a more nuanced take on the world. You’re not interested in AI slop—you want to make something meaningful.

There’s something implicit that comes through in the way people engage with Sublime, and seeing that makes me so, so happy. It’s easy to get caught up in questions like: why don’t we have 100,000 or a million users? But at the end of the day, it’s really about how many people you touch. That’s a much more valuable metric than reach. The business and economics of the internet aren’t structured in that way, so on a human scale perspective, it’s a really nice reminder of what actually matters.

Itay: Do you have a sense of why so many people actively want to engage with you, like writing about Sublime or joining the Slack? Because with most products, people might use them, but they don’t often engage more broadly. There’s usually a gap there. But with Sublime, it feels different. People actually want to be part of it.

Sari: I don't know. To be clear, we don't really have a head of community who manages and measures how many people are active on Slack. It’s kind of like a help desk, and then people are going to find each other. It's very organic.

I would flip the question over to you: why do you think that is?

Itay: I guess it's because I see a lively community. I'm part of a lot of communities, but I rarely check in on them because they're kind of dead. But every time I posted something in the Sublime’s Slack community, people responded—both publicly and privately. So yeah, I don't know… but it's a good sign.

Sari: I love that. I’d really love to build more of that into the product itself. The things that are resonating with you—those really matter. If we can get more people to collaborate and create together, that’s something I’d love to enable in a more meaningful way over time.

Itay: Speaking of communities, you recently talked at a fabulous event in Stockholm. How did it come about?

Sari: One of the main people planning the event, Lauren Crichton, is an avid Sublime user. It was amazing because it was one of those surreal moments. I meanEthan Mollick, Garry Kasparov, David Deutsch—all of these people were there. And I’m just here building this thing, still very much in spring/fall mode. It was amazing. I think it really speaks to how deep the love runs from people who truly get, use, and love Sublime. I’m just so grateful to Lauren—that whole experience was completely surreal.

Itay: I’m looking at the Sana website, and maybe I’m wrong, but at first glance, it seems like a product in a similar space to Sublime. How do you stay friends, not rivals, when you’re building something that feels kind of similar?

Sari: First of all, Sana is an enterprise knowledge management tool. It’s designed to help teams search and access their internal knowledge, more like an internal wiki. While we both care deeply about knowledge management and are excited about AI that lifts humans, I’d say from a product and customer standpoint, there’s basically zero overlap.

But I think your question goes deeper, and it's really about competition. Honestly, I don’t think about competition at all. Sure, there are alternatives, but if Sublime doesn’t work out, it won’t be because of them. It’ll be because we didn’t serve our customers deeply enough.

I actually think it’s riskier to spend too much time watching others. What helps us maintain a strong sense of identity is tuning that out and asking ourselves: what do we want to build? I didn’t set out to improve Roam or fix some other tool. I wanted to create something I’d fall in love with—a tool that helps me think better and engage more meaningfully with the world.

I think people worry too much about competition. Actually, one thing we’ve observed is that many people pay for multiple tools in our space. I really believe there’s enough room for all of us to win. Some people will love Sublime, some won’t—and that’s okay. There are so many nuances, whether you choose Notion, Readwise, or any other tool. Each one is designed for different kinds of people, and in fact, their existence helps shed light on the category and create space for us.

Personal niches

Itay: Before we wrap up, what’s a product, whether software or hardware, that you really admire for its design? Something that stands out to you as exceptionally well-made or thoughtful?

Sari: I appreciate how in the AI age, a lot of UX comes down to personality and feeling. When I think about Claude vs. ChatGPT, there’s an aesthetic sensibility in the former that stands out. It’s not just technically competent—it also feels cozy and intentional. That kind of personality and warmth in a tool really matters, and it goes beyond just the interface.

I also just got my Daylight in the mail a few weeks ago. With Daylight, what I admire most is the storytelling. Building hardware is incredibly hard (I’m sure subsequent versions will keep getting better), but the way they’ve crafted the narrative around it is what really impresses me. I believe people don't just buy products—they buy better versions of themselves. Using Daylight, I’m sort of stepping into a better version of myself. The fact that they've managed to build that is amazing

I’m also obsessed with Mercury. A lot of people in Silicon Valley, when Silicon Valley Bank had that run, were like, "leave Mercury and just go to a safe bank like Chase." And I was like, I can't give up this UX—it’s just too good. They've nailed all the details. I know where to find things, and it just works every single time. And I know how hard it is to make something feel that effortless. It's so delightful and continues to bring me joy.

Having said all of that, what mostly inspires me these days is experiences. Like this hotel in Stockholm called Ett Hem. Just the experience of walking in, how you feel, how they greet you, eating there… I don't think anything online remotely resembles that. Being in Stockholm recently and going into some of the stores, there’s this amazing Swedish brand I love called TOTEME. It’s so curated, beautiful, minimalist, and evocative. For me, it’s like walking into an amazing omakase restaurant, a hammam in Stockholm, or a beautiful retail space. That’s where I feel most inspired. It’s less digital these days.

Itay: Swedish design is something else. Everything that comes out of these Scandinavian countries is just so beautifully designed.

Sari: It's incredible, just the love of design there. You see it everywhere. There’s so much to learn, not just from the ideas, but from the experiences. For me, it was the way they savor meals, the slowness, the intimacy of small spaces. I was there for a tech conference, but what really stayed with me were the dinners—these 12-course meals that unfolded slowly, thoughtfully. It was nothing like anything you'd experience in the US. It was just amazing.

Sublime is now out of beta and open to the public. Extract your favorite highlights from this interview and add them to your newest collections.

psyched to be part of that community -of people who "want to make something meaningful" 🫶