Designing for a single purpose

What do a Dutch chocolate chip cookie and a thousand-year-old teahouse in Kyoto have in common?

If you’ve ever been to Amsterdam, you’ve probably visited, or at least heard about the famous cookie store that sells only one cookie. I mean, not a piece, but a single flavor.

I’m talking about Van Stapele Koekmakerij of course—where you can get one of the world's most delicious chocolate chip cookies. If not arriving at opening hour, it’s likely to find a long queue extending from the store’s doorstep through the street it resides. When I visited the city a few years ago, I watched the sensation myself: a nervous crowd awaited as the rumor of ‘out of stock’ cookies spreaded across the line.

The store, despite becoming a landmark for tourists, stands for an idea that seems to be forgotten in our culture: crafting for a single purpose.

In the tech scene where I’m coming from, and which you might too, this approach is often perceived as singular, and not in its positiveness. We’ve been taught to go big or go home—raise millions in funding, build a big company, hire more and more employees, and hope for the desired exit.

Anything less is considered a mind of a failure.

From a personal perspective I’ve seen this attitude in almost every branding session I ran with startup founders. Again and again, they struggled to distill their primary focus. Moreover, when discussing competitors, it often seemed their startup competed in every possible field.

In a way, that fear of committing reflects the human nature of FOMO—deliberately giving up on something(s) and experiencing the potential loss of other benefits.

This mindset has also seeped into our collective body of work, especially in software. A product, which often starts as a weird small creature, gradually evolves into a multi-arm octopus, which sadly became the norm for VCware1.

And so we’ve been left with bloated, bigger, and… worse software.

The idea of maintaining a small scope in product has already appeared in my writing in various forms; in niche product design I explored the effect of growth on design; and in defense of Twitter, I wrote about the bloated era of incumbent culture. But in between there seems to be a different attitude that not many choose to embrace, which like in Van Stapele’s case, seeks a real purpose.

Going back to basics as a way to find purpose

In a tweet posted a few months ago, Jeff Sheldon described his renewed approach to photography after getting a new camera. It enlightened my eyes:

I’m not a professional photographer, and never been. But my beloved Canon 700D still serves me often while traveling. Besides learning about ISO and shutter speed settings, being familiar with the mechanics of a DSLR camera has also introduced me to the practice of shooting photos in RAW format, which means capturing photos at the highest quality level.

But the super heavy file format marks only the start of the process in modern photography. The rest belongs to the post-processing act: the daunting work of polishing, enhancing, and fixing images.

When I returned from vacation, I hoped to edit my captures. Then I noticed something weird. When comparing my photos to some stunning photos I saw online, it seemed like my camera output wasn’t as good as those shared photos. In doubt of my gear I then, again, noticed something I should have probably known: it wasn’t about the camera, but the editing.

I realized professional-made photos were overly edited, often detached from their original conditions. It appeared that what you see isn’t what you get.

I wondered, has photography become an art of photo manipulation?

To respectful photographers, this might appear like a false accusation. The time spent sitting in front of the photo editor is at the heart of many camera enthusiasts. After all, that’s why a camera is set to shoot in raw.

But this potential debate triggers a more profound question: what’s the purpose of all this thing, to find the perfect angle or color filter?

Despite being somewhat contradicting with modern photography philosophy, I find “going back to basics”, as Jeff described, to reflect the same spirit as of Van Stapele—a devotion to a very minded process. No editing. No over-complication. Working only in one mode, and for the sake of it.

At first glance, Van Stapele’s laser-focused outlook might seem detached from tech and other mass-production industries. But there’s a line that can be drawn between the Dutch cookie store to some other products which makes them all distinct:

You can only read e-books with a Kindle.

There’s no app store on the Light Phone.

You’ll mostly find waterproof apparel in a Rains store.

The Bic pen has remained untouched for almost 70 years.

The design of Are.na remained the same for more than 12 years.

Whilst not every product mentioned above is hard-core focused like Van Stapele, the pattern is clear: an intentional commitment to a single purpose—either as a life philosophy, by using specific materials, or a deliberate design. And it also feels more appreciable when succeeding that way.

Some might call out a gimmick, while others appreciate the care for deep focus, which both are understandable. Finding the perfect recipe for the perfect cookie, and then committing to selling only that can be novel or a trick in marketing—depends on who you ask. But as I will stretch out from now on, I choose novelty.

We started with very minimal and basic products, aimed to serve only one simple job. A car to get from point A to B, a telephone to communicate with others, and a watch to check the time (perhaps the last analog device to serve human beings). But then many of our mundane artifacts have become more of a Swiss knife rather than just being exceptional in one form. We’re now drowning in oceans of product suites, both in the digital and physical worlds.

The bloated culture

In software, this trajectory is no different. Furthermore, it’s on steroids.

Despite “Do one thing well” being common advice for people building products in tech, it fails to hold water in the long run. Temptations are far too many to build and launch new stuff. Here’s Dropbox, a famous example of software turned bloated, in the words of DHH of 37signals:

Over the years, Dropbox has tried a million different things to juice upsells, seat expansions, and other ways to move the needle. There’s been a plethora of collaboration features (when all the collab I ever need is those magic links to files I can send over any wire!) and more and more pushy prompts to, say, move pictures and videos straight from the camera into the cloud. Along with pleas not to store the files I have in the system on my local computers (presumably so the transfer costs they pay are less). It’s exhausting.

I just want to pay for the original premise: All my files synched between all my computers, with a backup in the sky. That’s a beautifully, simply solution to a surprisingly difficult problem. And Dropbox absolutely nailed it.

Back in its heyday, Dropbox was simple. A classic piece of software. Its purpose was to allow people to store and share files on the cloud effortlessly—either from a computer or mobile device. It was straightforward. Even its homepage was simple. There were no bells and whistles. It was designed to serve… a single purpose.

But as with VCware, things have started to shift gears. Amid Google Drive's popularity, the “drop-to-the-box” identity started to blur as the product offering expanded.. and expanded. It seemed like Dropbox’s purpose became more generic and less focused.

Another resentment that ignited a storm in the design community occurred when the company announced a brand redesign a few years ago. In a way that act marked the shift in the company’s direction, bringing unclarity to its customers. The cynicism of Brand New's audience also made its review post one of the most popular that year.

The novel idea that was executed so well has followed the same growth patterns of the tech bubble—as I wrote in Niche product design:

As companies grow, they gradually move from a state of fan-only to a state of a product for everyone. During this transition, dramatic changes occur, as the drive to satisfy more audiences and increase revenue. But eventually, this shift harms the core of the product. It becomes scattered, and the brand turns into a gigantic octopus, leaving people questioning its purpose and values.

An email client, a note-taking tool, and a Photos-like app are only part of what Dropbox has been involved with over the years.

Today Dropbox is seemingly much more than a storage cloud service. It’s also a video reviewer (if there’s such a term at all), a Loom competitor, and a document e-sign tool. However, at its core, Dropbox is still a company selling terabytes on the cloud.

Yet Dropbox might be just a drop in the ocean. A symptom of a bloated culture in modern software. To better understand this bloat-mania, let’s look at one of its kingpins, and a company of which Dropbox is valued at 0.003%2 of its worth: Apple. And what’s a better example than one of its greatest products of all time, the iPhone?

Launched in 2007, the innovative touch-screen device had only essential features like phone calls, and text messaging among other luxuries like a camera, an internet browser, a weather, and a stock app. The peak of technology at the time.

In 2008, a year after the first iPhone release, Apple introduced the App Store, which was the catalyst for entering the smartphone era while unleashing a tidal wave of apps.

Fast forward to 2014, and the iPhone got an upgrade in the form of a multi-model release, with the launch of the iPhone 6 Plus. The trend expanded and Apple gradually added different shapes and names to the iPhone line: Plus, Pro, Pro Max, alongside other discontinued model names. This doctrine has been applied to many of Apple’s products—the iPad, Macbook, and Watch. Some got bigger, smaller, or faster. In a materialized world, I wouldn’t be surprised if the iPhone got bigger only to store more functions.

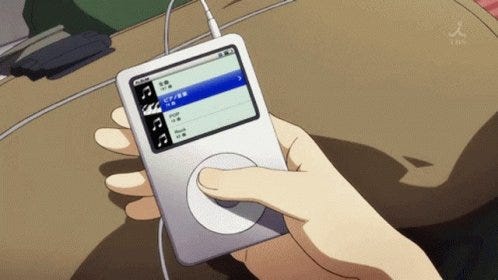

But perhaps the greatest archetype of Apple’s transition to bloated products was the iPod. The next-level MP3 (or 4?) essence was simple—to carry music on the road. Nothing more. But then Apple gave the iPod a life of its own, as it eventually became an iPhone replication, just without a SIM card.

The iPod (especially the non-touch model) is still dear to many Apple (non-)fansbois. The beloved product was designed entirely around the music experience. Before music streaming services took over the industry, people manually entered song metadata: the title, artist name, and of course—the holy album artwork. The hurdles of iTunes made this a daunting task, but iPod users found joy in this craft.

As a standalone product, disconnected from other functions, the iPod was a true single-purpose product.

In more recent times

What would happen if Van Stapele decided to add more flavors or open other branches? Probably nothing. Maybe its profits even increase. But the Valrhona3 chocolate-made cookie store icon will be losing its artisanal identity. Specialty and quality aren't determined by size.

In a more familiar case, we can look no further than the platform that hosts these very own words—Substack. Since the announcement of Notes, Substackers have shared concerns about the direction the platform is heading.

Substack’s original purpose, to some, was to highlight great writing while making writers a living. Now with the seeming transition for eyeballs and short-form content attention, Substack is being questioned whether modern social network dynamics are taking over it.

To close this social network loop—Twitter has been a good executer at designing for a single purpose until it wasn’t, largely by the decision of going for a longform direction alongside launching questionable features. For years Twitter sanctified the quirky 140-then-280-characters limit while establishing a new internet medium. Those recent announcements made by its new execs are ripping off its identity, slowly but surely. By adding more purposes to this platform design, Substack risks going down a similar path, jeopardizing its writer's soul.

Drinking beers and building businesses in Japan

If I were raised in Japan I may not understand what this turmoil is all about. The renowned business heritage in Japan is an oasis in the never-ending capitalistic desert:

Japan’s startup climate has often been criticized for being sluggish, perhaps because a culture that promotes business longevity also cultivates a fear of failure. Now, however, ‘startup’ and ‘atotsugi’ are words spoken in the same sentence, as today’s leaders finally feel permitted to apply entrepreneurial lessons to traditional companies to ensure their legacy continues.

Japan is located on the other side of the earth, and its business culture values seem too. In a Western society of hyper-everything, which characterizes the move-fast-and-break-things startup ethos, the far island culture is way more cautious. Instead of financial logic, which might seem irrational, the ‘shinise’4 tradition cultivates sacred values such as continuous improvement, longevity, and care for quality. It’s an extremely long-term game.

In Japan, more than 52,000 companies are more than a century old.

Japan is probably the largest home for centuries-old businesses, in varied fields from sake producers, to hotels and construction companies. This fact is much attributed to how generations of Japanese aspire to keep businesses running in the family5. But as in the words of Yusuke Tsuen, the current owner of Tsuen Tea6, the key to sustaining a shinise is to focus only on one thing:

“We’ve focused on tea and haven’t expanded the business too much,” he says. “That’s why we’re surviving.”

Why so many of the world’s oldest companies are in Japan, Bryan Lufkin

In The Price of Immortality Rohit Krishnan concluded the same:

The conclusion of this little digression has been to find common grounds amongst the most long lived organisations, and turns out you need to be a particular type of company:

Extreme dedication to doing one thing well

But the Japanese business heritage isn’t the last and only resort from bloat-ism. The next time you drink beer, think about this:

Weihenstephan is considered to be the oldest brewery in the world, founded in 1040, more than a thousand years ago. And we don’t need to travel this far back. Other European breweries like Tuborg (1873) and Heineken (1864) are over 150 years old.

Van Honsebrouck, the brewery that produces the famous Kasteel Rouge was founded in 1865 and is still owned by the same family.

The brewery is still owned and operated by the family, now the seventh generation of van Honsebrouck brewers in Ingelmunster.

Breweries have developed more tastes and flavors over the years, but they’ve been all operating for a single purpose for decades and hundreds of years: to craft beers.

What might come next?

A real shinise is rare in tech. Focusing on a single purpose often seems boring, a narrowed view, or a lack of ambition to some. But I find it invigorating. A long-lasting design can be timeless and unique.

Do we really want to carry our stress, depression, and fears everywhere we go? Don’t we want to feel disconnected from time to time? Then why the heck do we carry our mobile phones everywhere we go, even to entertain ourselves in the toilet? And not to mention the germs.

Would this all happen if we were using a cell phone that’s just designed to make phone calls? This is actually what the Light Phone founders realized a decade ago:

What does it do? Nothing. You put in a SIM card, press a few buttons, and make a call. There’s no browser. No games. No NFC. It has quick dial, which is nice, and it doubles as a flashlight.

The Light Phone Is The Anti-Smartphone, John Biggs

I may get carried away from the main idea of this essay, but that’s in part why I think designing for a single purpose is so important. The purpose of many products and artifacts has gone lost. Beyond the seeming gimmick, building for a single purpose reflects an understanding of what a thing is meant to be, and serve.

We’ve reached a point where focusing seems like spinning one's wheels, instead of appreciating the deep care of it.

And perhaps going back to basics is inevitable. When I’m reading on my Kindle I don’t get bothered by WhatsApp messages, or get interrupted by an incoming call. I’m not being tempted to do something else. I’m just focused on the act of reading.

As Devon tweeted a few years back: “When using my cellphone, I tend to become a passive consumer of the internet.” This also resonates well with the idea of this whole long text but from a slightly different angle. Using a multi-purpose product increases my distraction level, as I consume more things in the background.

Using a product that was designed for a single purpose brings back joy. It removes all the unnecessities and emphasizes an experience essence in a calmer environment, and with a real purpose.

Unlike photography, what you see is what you get.

Thanks for reading.

—Itay

Special thanks to kev for reading a draft and contributing to this post.

One last thing. If you find the above worth your time, consider supporting me with a coffee or sponsoring my gym membership 😎

Stephan Ango's term for VC-backed companies

At the time of typing these lines

The chocolate manufacturer which Van Stapele uses in its recipe

In Japanese shinise refers to long-established businesses that have been operated for at least 100 years

Business ancestry is an important value in Japan, called mukoyōshi. As in the story of Fusajiro Yamauchi, founder of Nintendo:

> Fusajiro Yamauchi did not have a son to take over the family business. Following the common Japanese tradition of mukoyōshi, he adopted his son-in-law, Sekiryo Kaneda, who then legally took his wife's last name of Yamauchi.

The history of Nintendo

A teahouse in Kyoto opened in 1,160 AD

I guess the challenge often comes from having the flexibility of changing the purpose itself. From serving great coffee to becoming third place the journey of changing purpose impacts the rest of what the org does.